Episode Notes

Jonathan Eig is the author of five books, including biographies of Lou Gehrig, Jackie Robinson, and most recently, Muhammad Ali. All three of them were New York Times bestsellers, and Ken Burns—yes, that Ken Burns—has described Jonathan as a “master storyteller.”

He and host Ted Fox met up at a diner called Stella’s, one of Jonathan’s favorite spots in Chicago, to talk about Ali: A Life, which Jonathan published with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2017. In addition to winning the PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing, the book was named biography of the year by the British newspaper The Times, one of the 10 best non-fiction books of the year by The Wall Street Journal, and one of The New York Times’ notable books of the year. It was also a finalist for an NAACP Image Award and received a whole host of other honors too numerous to list. If nothing else, just know that Joyce Carol Oates—yes, that Joyce Carol Oates—called it “an epic of a biography.”

Jonathan and Ted covered both Ali the boxer and Ali the icon, discussing everything from his trash-talking and what made him such a great fighter to his relationship with the Nation of Islam and what he’s meant in and to the broader culture since bursting onto the scene in the 1960s. They also spent some time on the process of researching and writing the book, including the painful parts, as well as what Jonathan asked Muhammad Ali when he finally got the chance.

LINK

Jonathan’s Biography of Muhammad Ali: Ali: A Life

Episode Transcript

*Note: We do our best to make these transcripts as accurate as we can. That said, if you want to quote from one of our episodes, particularly the words of our guests, please listen to the audio whenever possible. Thanks.

Ted Fox 0:00

(voiceover) Hey everyone, it's Ted. Just wanted to share a quick production note here at the top. We recorded this interview in mid-February, before Notre Dame moved to online classes, canceled events, and implemented social distancing practices in response to the coronavirus. With another couple of interviews already recorded, and the ability to record remotely, we plan to keep bringing you the show as usual, just with less brunch. So stay safe, and let's get to business.

From the University of Notre Dame, this is With a Side of Knowledge, the show that invites scholars, makers, and professionals out to brunch for an informal conversation about their work. I'm your host, Ted Fox. And if you'd like to keep up with the show in between episodes, you can find us on Twitter--and now Instagram, too. In both spots, we are @withasideofpod.

Jonathan Eig is the author of five books, including biographies of Lou Gehrig, Jackie Robinson, and most recently, Muhammad Ali. All three of those biographies were New York Times bestsellers, and Ken Burns--yes, THAT Ken Burns--has called Jonathan "a master storyteller." We met up at a diner called Stella's, one of his favorite spots in Chicago, to talk about Ali: A Life, which Jonathan published with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2017. In addition to winning the PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing, the book was named biography of the year by the British newspaper The Times, one of the 10 best nonfiction books of the year by The Wall Street Journal, and one of The New York Times' notable books of the year. It was also a finalist for an NAACP Image Award and received a whole host of other honors too numerous to list here. If nothing else, just know that Joyce Carol Oates--yes, THAT Joyce Carol Oates--called it "an epic of a biography." Jonathan and I covered both Ali the boxer and Ali the icon, discussing everything from his trash-talking and what made him such a great fighter to his relationship with the Nation of Islam and what he's meant in and to the broader culture since bursting onto the scene in the 1960s. We also spent some time on the process of researching and writing the book, including the painful parts, as well as what he asked Muhammad Ali when he finally got the chance. (end voiceover)

Jonathan Eig, welcome to With a Side of Knowledge.

Jonathan Eig 2:39

Thanks.

Ted Fox 2:39

(laughing) We were talking beforehand--I mean, you've been interviewed by Terry Gross and Ken Burns and Jon Stewart, so I'm sure this one is right up there.

Jonathan Eig 2:49

Well I'm more nervous for this one.

Ted Fox 2:51

(laughs) I'm asking you to read right away, so ...

Jonathan Eig 2:53

Yeah, I don't like that.

Ted Fox 2:54

(laughs) So I wanted to start by asking you to read a passage from your book Ali: A Life. And this is Ali arriving in Zaire in 1974 for the Rumble in the Jungle fight against George Foreman.

Jonathan Eig 3:08

Okay, here it goes. "Immediately, Ali began working the audience. Africa did not play a central part in the story of the Nation of Islam. The Nation of Islam talked about Black Americans returning to their Asiatic roots, not their African roots. But Ali had always had a brilliant instinct for shaping his own biography. He had long ago discarded his American name and challenged the American government's right to tell him what to do. 'I'm the king of the world!' he had shouted after beating Sonny Liston in 1964. He had not said king of America. King of the World! Most men and women invent their identities by the time they reach adulthood. In the story of Ali's invention--shaped by his Jim Crow childhood, his rambunctious father, Elijah Muhammad's religious vision, and Ali's own grandiose appetite for attention--he was the African American King, and he had come to Zaire to please his people and to retake the crown that obviously belonged to him. Most men and women don't know they're making history until after they've made it, but Ali worked on the simple and liberating assumption that he was always making history."

Ted Fox 4:12

Thank you for reading that. Why was Ali's history, Ali's story, one that you wanted to tell? Because as you reference in the notes to the book, it's not like he hasn't been the subject of biographies. Why did you feel that you needed, wanted--and you're a writer, you probably felt compelled to--why was he a subject that you turned to?

Jonathan Eig 4:33

I loved Ali as a kid, and everybody loved Ali. In the '70s and '80s, he was the most famous man on the planet, most likely--maybe the pope. But I think Ali was more instantly recognizable, and he used to talk about it all the time. Like, he'd say, If I parachuted out of a plane anywhere on Earth, and I just walked to the nearest village, they would know me and they would welcome me and they would love me. And he had that attitude. And he was such an important figure, you know, in our culture and world culture--you know, a radical when it came to religion, when it came to race. And it just stunned me when I realized that there had not been a proper, full-blown biography. There've been, you know, hundreds of books about Ali, but they all took a slice, a piece of the story. And when I realized that, you know, nobody had done the full biography, I just couldn't believe it, and if I could be lucky enough to do that job, man, I'd be the happiest guy on Earth.

Ted Fox 5:26

Yeah. And you did do the job--it's a tremendous book. One thing that--so the piece that I asked you to read there before the fight with George Foreman, it was on full display before that fight, before his fights with Joe Frazier, before his fights with Sonny Liston: He liked to talk trash. And he did so in ways that were legendary--you know, "I'm the king of the world," "I'm the greatest," "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee"--and as you get into in the book, also ways that were highly problematic, especially against other Black fighters. What relationship, in your time you spent thinking about him and writing about him, what relationship did Muhammad Ali the trash-talking heavyweight champion of the world bear to Muhammad Ali the man?

Jonathan Eig 6:13

It's a big part of understanding Ali. Because he's so lovable, and he's so desperate for attention, he wants everybody to love him, and at the same time, he's constantly trash-talking. Sometimes it's good-natured, like with Howard Cosell. But with his opponents, it's not good-natured. It's really mean. And it's not clear whether he does this to pump himself up, whether he does it to undercut his opponents. One of the really interesting things is that he only really did it against Black opponents. He didn't try to insult the intelligence of his white opponents. And one of the people I interviewed--a trainer, a boxing trainer who knew Ali really well--he said he thought Ali was doing it out of a sense of insecurity. That Ali--you know, most boxers come from poverty, most of the Black boxers are tough guys from the ghetto, and Ali was not. He was a middle-class kid, and maybe he felt like he didn't have the same status that they had. Maybe he felt like he didn't have the same ...

Ted Fox 7:10

Almost like a street cred kind of thing.

Jonathan Eig 7:12

Street cred. And he had to overdo it with his trash-talking to act as if he was tougher than those guys. I don't know. It's an interesting theory.

Ted Fox 7:22

Well, there's a section in the book where you basically include most of, a big chunk of a transcript of a drive that he took from Philadelphia to New York with Joe Frazier. And it's really interesting just to watch them at length interacting with each other. And I mean everyone now, of course, even if you know just a little bit about boxing, you know just the way he tortured Joe Frazier with his words. And to see them--you could speak much better to that private relationship--I don't know if you'd call them buddies. But they weren't--it wasn't a combative car ride. I mean, Ali I think at one point asked him if he could borrow some money because he needed some money. And it was just an interesting window into what they were, privately at least, before the rivalry blew up to what it became.

Jonathan Eig 8:10

I love that scene with the two of them in the car, and in fact, you know, I had to pay a lot of money for the rights to use that. (Ted laughs) And I really debated whether it was worth that money out of my own pocket, but it was. Because you see them in a way--and Ali still knew there was a tape recorder going, and his ghostwriter for his autobiography was in the backseat of the car, so it's not completely unfiltered--but nevertheless, there's a kind of an intimacy there. And you see that there's a real affection between the two, and Ali clearly liked and respected Frazier. But when it came time to fight, and when it came time to put on a show, he got really, really mean in a way that truly hurt Joe. Because Joe thought, Hey, we were friends. And I think that tells you a lot about Ali, that he could be really callous toward people that he seemed at one time to care about--including, you know, Malcolm X, who was one of the most important influences in his life, and Ali completely turned his back on Malcolm X and may have, you know, had a chance to save Malcolm X's life and didn't take that chance.

Ted Fox 9:09

I mean, I'm glad you brought up Malcolm X because Ali's relationship to the Nation of Islam went way beyond--I think, again, if you knew nothing else about Ali, you probably knew, Okay, his name was Cassius Clay. Which as you point out, was actually a name he really liked a lot; he liked his name, Cassius Clay. But, as you also point out, when Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation, told him, You're changing it to Muhammad Ali, he did so without hesitation. It's like, Okay, you know, the leader said this, this is what I'm doing. What was the Nation--and this is a really big question--but what was the Nation of Islam, I guess in kind of the broadest terms, to Muhammad Ali?

Jonathan Eig 9:48

I think it gave him a bigger sense of himself. And he was always somebody who struggled because he wanted attention, and he wanted to rebel. He wanted to be loved, and he wanted to be confrontational. Which seems to be oxymoronic, right? But he made it work somehow, in a way that was truly unique to him. But the Nation of Islam gave him these guiding principles. It gave him something bigger that he could believe in. He believed that Elijah Muhammad was a prophet of God and that Elijah Muhammad had a path to independence, to freedom for Black people, that did not rely on the white man's permission and the white man's system. And that was really appealing to Ali. It gave him discipline, it gave him a sense of believing in something bigger than himself. And it allowed him to be a radical, to break away even from the mainstream civil rights movement. So a lot about it appealed to him.

Ted Fox 10:41

I think it's interesting because today with the benefit of hindsight--or maybe even not hindsight, maybe the way history kind of tends to sand the edges off a thing--but today, Ali is beloved by a really wide swath of people and cultures. But that wasn't always the case, particularly in the 1960s. How did America think of--I guess when the '60s started, he was Cassius Clay, and then he became Muhammad Ali, there was everything with him, you know, refusing to go in the draft and all these things--how did America writ large think of Muhammad Ali in the 1960s?

Jonathan Eig 11:22

You know, they didn't like him much to begin with when he was Cassius Clay because they thought he was a loudmouth, and they thought he was a bad sport, mocking his opponents, predicting the rounds, this was unsportsmanlike behavior. And it didn't play well, especially with the white media. Black people tended to like it because he was being rebellious. But when he became a contender for the heavyweight crown, he drew great crowds, so it was good for the sport. And he was getting away with it. But then when he began hanging around the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, the white reporters couldn't tolerate that, that was just a, you know, bridge too far for them. And in fact, you know, when he announced after winning the heavyweight championship that he was joining the Nation of Islam, made it official, he became one of the most unpopular men in America, certainly among white people. And then he compounded that by saying that his religion forbid him to fight in Vietnam and that he was going to object to being drafted.

At that point, you know, you start to see repercussions. He loses his boxing license, he's convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison. And he goes three-and-a-half years without boxing. And this is really, it looks like it's the end of his career. And this is really, you know, Ali at his lowest. He can't make a living, he, you know, takes to college campus lectures to try to scratch some money together. And he doesn't really believe he's ever gonna box again. You know, we always talk about how, you know, Ali was in the desert for three-and-a-half years and couldn't make a living, couldn't box, lost the prime years of his career, but it's important to remember that he didn't know it was gonna be just three-and-a-half years. He thought it was over, that it was permanent, and that he would never box again, and he was willing to make that sacrifice. So all during that time, he's, you know, incredibly unpopular and becomes sort of a political football. Politicians won't let him box in their state because, you know, he's public enemy number one to them.

Ted Fox 13:22

The story in the biography, too, of how the Supreme Court came to basically overturn his conviction for draft evasion was interesting because they're weighing these--I mean, one, it ends up being a conservative justice who reads, I think it was Elijah Muhammad's book, and kind of starts to question maybe the merits of what was going on here. But it wasn't necessarily an ideological stand the Supreme Court was taking; it was more of a: How can we resolve this without setting this huge precedent that, well, everyone's now going to say they're a member of the Nation of Islam to avoid going to Vietnam?

Jonathan Eig 14:03

It's fascinating because it's one of the few instances in which you'll see justices of the Supreme Court admit that they're looking for a political way out of this problem, that it's gonna look really bad if they send Ali to jail without giving him a trial, that if they just confirm the lower court's ruling, Ali goes to prison. And they're looking for a way out because that, you know, it's gonna look like they just did this to punish him, they're gonna look like they're a bunch of racists, and they don't want that to happen. The justices admit that. So they find a technicality to let Ali off the hook. And they intentionally want to find something that won't set any precedent because they know that they're just like--they're playing fast and loose a little bit with the rules here. So Ali gets off on a technicality.

Ted Fox 14:45

And I mean if I'm remembering right, or I understood right, wasn't that technicality basically, You didn't really say why he was being punished--like you didn't give, the lower court or whoever when the charges were pressed, they didn't say specifically why he was being convicted of this and therefore they had to overturn it?

Jonathan Eig 15:03

Yeah, exactly. So it was really, they were really cutting it, cutting it ...

Ted Fox 15:09

(laughs) But they voted eight nothing.

Jonathan Eig 15:10

Yeah. Right. Because they wanted it to look like they were--it's fascinating, it's one of the really interesting chapters in legal history. And they avoided setting a precedent, as you said, they didn't want to make it seem that if you just joined the Nation of Islam, you could avoid serving in Vietnam. So they dodged that bullet.

Ted Fox 15:26

Right. So Ali was, he was an athletic icon, he was a social icon, he was a cultural icon. But in terms of the relationship to the women in his life, and there were many women in his life, he wasn't someone that we would say that we would look up to, at least during those years when he was active as a fighter, when he was, you know, in those years of his career. To your mind, how does that part of his story fit into the broader legacy of Muhammad Ali?

Jonathan Eig 15:57

It was painful to me to see how badly he treated women, even how badly he treated his children. He wasn't, you know, he wasn't around for the kids. But the biggest issue and the biggest thing I struggled with as an Ali fan, was talking to his wives and seeing how really badly mistreated they were. And wasn't just that he cheated on them. You know, he used the women against each other, he expected them to cooperate, he expected-- you know, he had one wife who was basically setting up dates for him with other women and was expected to tolerate that other women were going to travel with them when they went overseas. You know, he was sleeping with just, you know, a lot of women at the same time. And even, you know, there's a story, an allegation, of a much younger woman, you know, a girl who's a minor, who he allegedly impregnated, and she sued over that. There's things in there that were just, you know, really difficult for me to understand. But my job is not to sugarcoat it; my job is to lay it out there for the readers. And I worried that the readers after reading some of this stuff we're just going to have a hard time liking him again as the book went along. But again, you know, the biographer's job isn't to spruce up or to take down his subjects; it's to tell the truth. And I just have to put it out there and let people judge for themselves how they feel about the guy.

Ted Fox 17:21

Yeah.

(voiceover) Taking a quick break here to tell you about the Democracy Group, a new podcast network that features shows focused on civic engagement, civil discourse, and democracy. The network includes two podcasts that, like ours, are produced at universities: Democracy Works from the McCourtney Institute for Democracy at Penn State, and Democracy Matters from the Center for Civic Engagement at James Madison. Information about all member podcasts is available at democracygroup.org. And now, back to the show. (end voiceover)

Ted Fox 18:00

Can you give a sense of all that went into writing this book?

Jonathan Eig 18:04

(laughs)

Ted Fox 18:04

I mean, I know, for instance, that there were a couple research projects that you commissioned on the punches he threw and was hit with throughout the course of his career and changes in his speech pattern over time. And it also seemed like you watched an awful lot of boxing (laughs), probably, in order to write this.

Jonathan Eig 18:22

This was so much fun. It's the first book that I did where the majority of the people close to Ali were still alive. You know, my other books were much older subjects. So you know, in writing about Al Capone, I met only a few people who'd ever, like, seen or met him. Lou Gehrig, same thing--you know, a couple dozen people who'd met Lou Gehrig. But for Ali, I interviewed hundreds of people who knew him really well. And I spent hours and hours, dozens of hours, with his wives, with the people who were closest to him, with his opponents, it was just a blast. But as you suggested, I also--I counted every punch that he was hit with and every punch that he hit his opponents with. And then I used that to calculate how many punches he was likely hit overall, if you count amateur fights, sparring, and everything else. 200,000 is my best guess, that he was hit 200,000 times. And then I worked with speech scientists. I mean, I just felt like this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to write a biography of Ali, and I wanted to make sure that I left nothing out. Not everything goes into the book, I didn't want the book to be 4,000 pages long. It's already pretty long. But I wanted to make sure that I covered everything that I could cover, that nobody would come in behind me and say, But he didn't do that.

So I actually worked with speech scientists to study Ali's patterns of speech to see when he began showing signs of brain damage. There's some scientists at Arizona State University who had done this with Ronald Reagan. They'd analyzed his press conferences, and they were able to determine approximately when he began showing signs of Alzheimer's. So I asked them if they could do the same thing with a boxer, and they loved the idea. I sent them hundreds of YouTube videos of Ali in chronological order, and they measured syllables per second as well as the amount of mouth movement, several different factors. And they were able to determine what Ferdie Pacheco, Ali's fight doctor, said was true: that he began showing signs of brain damage in the early '70s, 10 years before his career ended. So for a whole decade, he's fighting with signs of brain damage, and you can chart it, fight by fight. You can tell based on his speech patterns which fights he took the most punches, and it all correlates. It's just devastating.

Ted Fox 20:24

That was one thing that was striking in reading the book was the number of fights in the '70s where either leading into it or right afterwards--Okay, this is it, like, I'm done after this. And it was always invariably, Well, I guess a couple more, and you just see this kind of build. And I'm glad you brought up Ferdie Pacheco because that was the interview that you did in particular that I wanted to ask you about because it really struck me. So he's Ali's ring doctor, and he resigned from that post after the '77 fight at Madison Square Garden against Earnie Shavers because he thought Ali was, what he was doing was going to permanently damage his brain. And you asked him if he told Ali this, did you say to him that he was damaging his brain? And the way you wrote it was: "'Yes, I told him,' Pacheco said, his voice rising in anger, his body coming out of his seat as he spoke." I was wondering what that moment was like for you, as an interviewer, because that detail of how this doctor was conveying this information to you certainly seemed like even after all these years, he really wanted to convey, No, I was a voice in the wilderness standing there going, like, no, you need to stop doing this, and people need to understand that we were trying to stop him. And I just imagine as an interviewer, it was a really kind of intense moment to be a part of.

Jonathan Eig 21:47

It was intense in several different ways. (laughs) Because he didn't really want to do the interview.

Ted Fox 21:52

Yeah.

Jonathan Eig 21:53

And it was one of my first interviews. I went to his home in Miami Beach. And when he sat down, his wife told me, like, he doesn't want to talk about Ali. I said, Well that's what I'm here for; what am I gonna do?

Ted Fox 22:03

(laughs) What else are we doing here?

Jonathan Eig 22:04

So I figured, alright, we won't talk about Ali, and I'll try to ease into it. And when I started talking about Ali, he said, I don't wanna talk about that. I said, Well, you know, Dr. Pacheco, I mean, I see all these history books on your wall, you've got this great collection of history books--Ali is history. And you were there. I mean, you were a living witness; I really, I need to ask you a few questions. And he just got angrier and angrier. And finally I said, This is gonna be a really short interview, I better just go for the big question right away--like, you know, I gotta go for the knockout punch here, and I have to stop trying to be subtle about it. So I said, Why'd you let him keep fighting? And, you know, I just knew I was gonna provoke him, that I was going to be kicked out at any minute, so I just went for, like, the questions that I most needed to know. And I said, You're a doctor, you know, why? He said, No, I'm a fight doctor--the fight doctor's job is to put the fighter in the ring; they don't pay me to say he shouldn't be fighting. I thought, Man, that's like, how do you even be a fight doctor? Should there be such a thing as a fight doctor? It seems like, you know, it's an oxymoron.

Ted Fox 22:19

Right.

Jonathan Eig 22:25

That's the second time I've used that word in this interview; I don't think I've ever used that word twice in one day. (Ted laughs) Anyway, it was really fascinating. You could just see that he was still really torn by this role that he'd played. And to his credit, he was the first--and for a long time, the only one--to speak up and to try to stop Ali from boxing. Everybody else went along with it because there was money in it, because there was fame in it, because they got to be on the circuit, you know, with all the girls in the hotel rooms, and being around Ali was fun. So Pacheco was the only one who said, No, this has to end. And he actually quit.

Ted Fox 23:42

Right. When you feel an interview going that way--for me, I think as an interviewer, I would feel awkwardness but also that I need to push through it because I need to get to this answer. Does that get easier over time? Or is it always kind of a: Wow, okay, I'm about to have a really uncomfortable conversation with someone, but that's what I have to do to get the information that I need?

Jonathan Eig 24:05

Yeah, I feel like I'm a fighter in this; I just need to last this round. And if I can get to my stool, you know, you never know what's gonna happen the next round, I might get lucky and land a good punch and turn things around. And that's what you do. Like, I interviewed John Ali, who was the second to Elijah Muhammad in the Nation of Islam and allegedly an FBI informant, and some people would say may have known about the plot to kill Malcolm X. Getting anything out of him was really hard. And on the one hand, you don't want to just come out and say, you know, What did you know about the assassination of Malcolm X? Because that could end the interview.

Ted Fox 24:41

Yup.

Jonathan Eig 24:41

But you also don't want to be too polite and skirt the question to the point where, like, you get out of the interview and say, Why didn't I ask him that? So it really is, you know, I think of it as a boxing match in a lot of ways.

Ted Fox 24:53

(laughs) It's the sweet science.

Jonathan Eig 24:54

You got to keep your distance, you got to use the jab to buy yourself some time, and then if you see an opening, you gotta throw the punch.

Ted Fox 25:01

Mm hmm. You talked early on about, you know, the reason why you did this is just because you grew up loving Muhammad Ali. And now you spent all this time watching all these bouts that he had. And I know you're not a boxing historian specifically, but what to you, after watching all this--and you even showed some stats where this service called CompuBox, maybe he wasn't the greatest heavyweight of all-time, maybe by certain metrics or whatever else--but what to you after watching him, what made him such a great fighter?

Jonathan Eig 25:37

Yeah, I don't think he was necessarily the greatest boxer of all-time. But he had this unbelievable, almost like a jazz musician, this ability to improvise, and to find the way to beat almost every opponent. And unfortunately, so much of that rested on his ability to take a punch because he could hang in there until he figured out how to win this fight. And so you see, there's beauty in that ability. But you also see the ugliness and that this great gift is also the thing that hurts him the most.

Ted Fox 26:10

In conjunction with the book, you did a podcast--I have to ask about a podcast, of course--called Chasing Ali that takes listeners kind of in these smaller vignettes inside the actual process of this journey of writing this book. And one of the episodes--so I have to back up for a second. One of the questions when I was originally reading the book that I was like, I'm gonna ask him is, Oh, if he had the chance to ask Muhammad Ali one question, what would it be? (Jonathan laughs) And then I found the podcast where you actually went through this process because you thought that you were gonna have a chance to maybe meet him in Louisville. And you're spending all this time thinking like, Okay, like, I'm probably going to get one shot at this, if I get any shot, and you're working with his wife, Lonnie, to try and make this happen. And then it finally does, I think it was less than a year before he died. And because of his declining health, and because it's at a public event where there's a lot of commotion around, you talked about how he wasn't able to respond to you. I mean, you're right there next to him, but you don't really get any kind of acknowledgment of, Oh, he heard this or he could say something back to me. What did you say to him? And I'm wondering, as someone who grew up loving him, you spent all this time, how did you feel walking away from that interaction, which clearly, it didn't go the way in your head probably that you were hoping or even thought that it might go?

Jonathan Eig 27:30

Yeah, I desperately--you know, I spent four, four-and-a-half years on this book. And I spent two or three years trying to meet him, chasing him around the country, going to events where he was supposed to be there and trying to get the time with him just to let him know that I was working on this book. And then once I got to know his wife, and once I went to his house, but he was too sick, he didn't come out of his room. This is the long ordeal of trying to meet him. And all of that time thinking about, What am I going to say to him? If I can ask one question, what's it going to be? And knowing that he hadn't done an interview in more than a decade, he wasn't going to have a long chat with me. He wasn't going to, in all likelihood, he wasn't going to be able to answer a lot of questions. So if you could just ask him one question, and you might get a short answer from him, what would it be? And I really--I mean, I had asked my friends for suggestions. I, you know, I was really tormented by this. And I didn't really decide until the day that I met him. I went for a run in Louisville. I was supposed to meet him that night. And I went for a run along the same stretch that he used to run, one of the stretches that he used to run, not in his neighborhood but near his high school. And as I was running, I said, This is stupid. (laughs)

Ted Fox 28:45

And I loved this part of the episode that you did.

Jonathan Eig 28:48

Oh, thanks.

Ted Fox 28:48

It's just such a writer thing to think like, Alright, I'm gonna recreate this, and it's just gonna come to me, and then you're like, Wait a minute, why would this make me think of the perfect question to ask him? (laughs)

Jonathan Eig 28:55

Right, right. And it's something that we do--you know, on the one hand, you want to see the path that he ran along, right? You want as the biographer to try to see things from his perspective. And Robert Caro tells this great story about walking the path that LBJ used to walk to the Capitol every morning, and there was a certain point that LBJ used to actually start running. Caro walked it and saw that as the sun was coming up over the over the Capitol, there's this beautiful sunrise, and it must have just inspired LBJ to break out in a run. And Robert Caro had to walk in that path at that same time to understand it. So you want to try to understand your character as much as you can and see things from their point of view.

But then as I'm running, I'm thinking, Here I am this little white boy from New York who thinks, you know, in 2015 that he's going to, you know, run in Ali's footsteps and actually understand what it was like to be a kid growing up in [the] Jim Crow South. Come on, give me a break.

Ted Fox 29:49

Right.

Jonathan Eig 29:50

And that's when I thought of what I should say to him. You know, it occurred to me that I needed to humble myself. So when I finally met Ali that night, his wife introduced me, and as you said, there was a commotion, there were other people waiting to meet him. But I was the first to get to his table that night. I put my hand on his arm, and I whispered in his ear. I said, Muhammad, my name is Jonathan Eig, and I'm writing a book about you, and I'm trying my hardest to do it right and tell your story the way it deserves to be told. And I just want to know if there's anything you want to say; the last word in the book should be yours. And he didn't answer. And in a way, you know, you asked me how I felt--I felt tremendously relieved, first of all, that I got to meet him. And that I could say that I spoke to him. And that I looked him in the eyes and told him I was doing this book. I felt like that was, at least selfishly, that was really important. Probably didn't mean anything to him. But as far as him not answering, I also felt like that was Ali, you know? Ali never made it easy on anybody. He didn't make it easy on his wife, on his opponents, you know, and he wasn't going to make it easy on me, he wasn't gonna give me my ending for the book. I had to do it myself. And that's okay.

Ted Fox 31:02

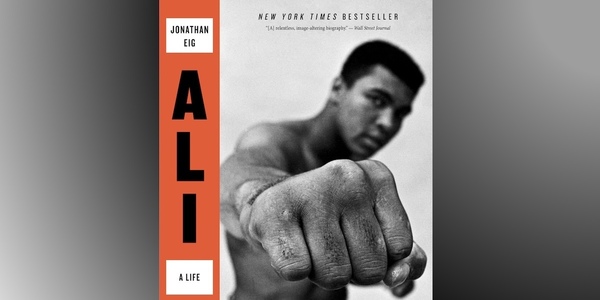

The cover of the book, it's a black-and-white photo of a young Ali from the torso up, and his right fist is extended towards the camera. And it's the fist that's in focus, it's not his face. What does that photo mean to you?

Jonathan Eig 31:19

I love the photo, I love the design of the book, I think it's gorgeous. I had originally in my mind, you know, as you're writing these books, you have a picture in your head of what the book is gonna look like; I thought it'd be a color photo. I thought it'd be a very modern look. And they went totally classic, old school. And I think it's great. And, you know, nobody's ever asked me that before: What does it mean for Ali to be out of focus and for his fist to be in focus? You know, Ali was so many things to so many different people. You know, he was a religious icon. He was a Black radical icon. He found a way to seem almost like an everyman. It reminded me a little bit of Chauncey Gardner in Being There, the Kosinski book and the movie with Peter Sellers. Like, no matter what he did, people found a way to connect with it. And that was part of the miracle of Ali. And I think the fact that he's out of focus in that way might be appropriate that it, you know, we each bring our own focus to Ali.

Ted Fox 32:17

And I love, too, just kind of the, by virtue of the prominence of the fist, and there was--I mean, because you talked at different points about him being a fighter. And I mean, in a very literal sense, he was a fighter, but was a fighter for much bigger issues, too. And there was a paragraph near the end of the book where I think your writing of it is beautiful, and I thought, it's short, but it really captures some of that essence. So I wanted to go ahead and ask you to read that here as we wrap up.

Jonathan Eig 32:49

Sure. "Some writers said that Ali had 'transcended' race. It was an attempt to whitewash his legacy, and it was dead wrong. Race was the theme of Ali's life. He insisted that America come to grips with a Black man who wasn't afraid to speak out, who refused to be what others expected him to be. He didn't overcome race. He didn't overcome racism. He called it out. He faced it down. He refuted it. He insisted that racism shaped our notions of race, and that it was never the other way around."

Ted Fox 33:21

The book is Ali: A Life. Jonathan Eig, thanks so much for doing this. And thanks for having me to Chicago; it's fun to go to a new diner to do an interview. So thank you.

Jonathan Eig 33:31

Oh, thanks for coming to Stella's, and it's great talking to you.

Ted Fox 33:34

(voiceover) With a Side of Knowledge is a production of the Office of the Provost at the University of Notre Dame. Our website is provost.nd.edu/podcast.