Episode Notes

This is our season 4 finale, and we’re taking a look back—not at the history of this podcast, but at the history of fashion, and our guide is a great one.

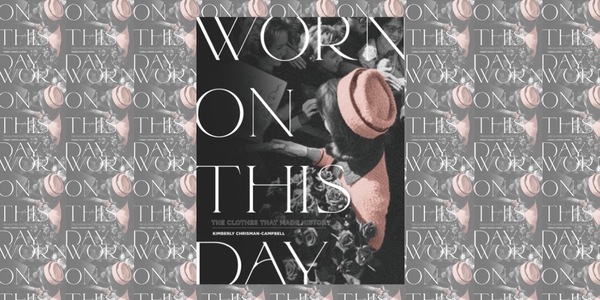

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell is an award-winning fashion historian, curator, and journalist and a 2020–21 National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Politico, and The Wall Street Journal, and she is the author of three books, including Worn on This Day: The Clothes That Made History, which had its origins as a Twitter account and was published in 2019 by Running Press.

While we had a lot of questions for her about Worn on This Day—how she found an article of clothing tied to every day of the year, what kind of history this approach allowed her to write, why she picked what she did for the September 11th entry—we also talked about the distinctive role fashion plays in the human story.

We asked Kimberly about her NEH project, as well, and learned a little bit about American fashion designer Chester Weinberg, whom she’s hoping to reintroduce to a large audience. And then there was her most recent book, The Way We Wed: A Global History of Wedding Fashion, a sequel of sorts to Worn on This Day.

Fun fact there: The white wedding dress? Not as traditional as you might think.

LINKS

- Kimberly’s Books: Worn on This Day: The Clothes That Made History and The Way We Wed: A Global History of Wedding Fashion

- Worn on This Day Twitter: @WornOnThisDay

Episode Transcript

*Note: We do our best to make these transcripts as accurate as we can. That said, if you want to quote from one of our episodes, particularly the words of our guests, please listen to the audio whenever possible. Thanks.

Ted Fox 0:00

(voiceover) From the University of Notre Dame, this is With a Side of Knowledge. I'm your host, Ted Fox. Before the pandemic, we were the show that invited scholars, makers, and professionals out to brunch for informal conversations about their work. And we look forward to being that show again one day. But for now, we're recording remotely to maintain physical distancing. If you like what you hear, you can leave us a rating on Apple Podcasts or wherever you're listening. Thanks for stopping by.

This is our season four finale, and we're taking a look back--not at the history of this podcast, but at the history of fashion, and our guide is a great one. Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell is an award-winning fashion historian, curator, and journalist and a 2020-2021 National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Politico, and The Wall Street Journal, and she is the author of three books, including Worn on This Day: The Clothes That Made History, which had its origins as a Twitter account and was published in 2019 by Running Press. While I had a lot of questions for her about Worn on This Day--how she found an article of clothing tied to every day of the year, what kind of history this approach allowed her to write, why she picked what she did for the September 11th entry--we also talked about the distinctive role fashion plays in the human story. I asked Kimberly about her NEH project, as well, and learned a little bit about American fashion designer Chester Weinberg, whom she's hoping to reintroduce to a large audience. And then there was her most recent book, The Way We Wed: A Global History of Wedding Fashion, a sequel of sorts to Worn on This Day. Fun fact there: The white wedding dress? Not as traditional as you might think. (end voiceover)

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, welcome to With a Side of Knowledge.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 2:05

Thank you.

Ted Fox 2:07

So clothing and fashion are all around us every single day. And maybe for that reason, they're things that can easily get taken for granted; we might not consciously notice the cut of a dress or the color of a shirt or how a particular item moves. And yet in the preface to your book Worn on This Day: The Clothes That Made History, you wrote "Clothes reveal ineffable truths about not just individual lives, but also collective values and experiences." What do you find distinctive about clothes as cultural artifacts? And what can we maybe learn from them that we might otherwise miss?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 2:42

Well, clothing is a wonderful way to study and experience history because it's something that we're all experts in. We all have clothes in our house, we wear them every day. That's not true of other kinds of art that I've worked with, like snuff boxes or sculptures, things that we don't necessarily have on hand and interact with on a regular basis. But clothing is certainly part of our lives, it's something we can all look at from a place of expertise, if only to say, I would never wear that, or I would love to wear that. The problem is the things that survive don't necessarily reflect what we wear all the time; they tend to be things that are preserved for sentimental reasons, like a wedding dress or a letterman jacket, or things that maybe survived by accident because they got left in the back of a closet or in a trunk in an attic. Or perhaps they're things that didn't actually get worn very much because they were too trendy, or they were a little bit too tight, or they just were too nice to throw away but were for a special occasion and not actually something that was worn on a regular basis. And all that is true of things that find their way into museums. And of course, the history of museums is fraught with all sorts of racial and class issues. So the things that got preserved and saved tend to reflect the clothes of the very wealthy.

Ted Fox 4:01

You know, we were talking before we started recording--or started this version of the recording--and you gave a really good example of how, you know, when you're talking to someone how you can think about that, and thinking about what's in your own closet. And you know, truth be told, even though I have this background up, I am recording, I record all these episodes in season four, in my wife's closet. (both laugh) So I'm in a closet with clothes all around me right now, and you kind of gave this example of, Think about your own clothes and what might make it through four or five years, and what might kind of just fade away that you would never have any record of even having owned then.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 4:36

That's right. Curators love to think that museum collections are full of the things that represented the perfect, most, you know, beautifully preserved example of fashion at the time, and that's just not true. And you can think of your own closet and the things that have been there for three or four or five years. They're not your everyday clothes; those got worn out and thrown away or donated. They're things that you didn't wear very much or things that you saved for a sentimental reason rather than because it was the most perfect example of what everybody was wearing at a certain time and place.

Ted Fox 5:09

And as a result of that, then--because I mean, you talked about racial inequities, etc., in terms of the things that have gotten preserved or that end up in museums. I mean, is the gap when we're looking back, is it typically associated around people who would have been working class and we've preserved kind of more the beautiful things of high society? Or is it kind of across the board that we just end up with these gaps in our knowledge of what people people were--I mean, I'll confess that most of my knowledge of like, you know, real high society fashion is probably from things like Bridgerton (both laugh) and things like that from, like, the first part of the 19th century. But are the gaps kind of concentrated among people who would have just really been working for a living, or are we kind of missing swathes across all kinds of different sorts of people?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 5:57

There's all kinds of different gaps. Typically, preservation tends to favor the beautiful and the unusual. So museums are full of wedding gowns, they're full of evening gowns, things with amazing embroidery and beading. And it's not necessarily because of, you know, racial or class prejudice so much as, many museums were founded as a way to preserve the decorative arts. A local history museum would have a much different collection from the Met, for example. Because their priority is to find things that were worn locally and that had local history importance, belonged to local families, not necessarily that they were the most beautifully made, most high-fashion pieces. Whereas a museum like the Met or the Victoria and Albert Museum, they collect for the artistry of the clothing, which automatically privileges, you know, the very wealthy. And those of course were the people who were donating to museums in the 19th century, when the museums were being founded all over the country and all over the world.

Ted Fox 6:56

Right. So Worn on This Day, you note that the items you're putting in this book, in this fashion history that you're creating, they're in there based on a single criterion: the date that they were worn. What does that free you up to do, then, in terms of the fashion history that you're telling?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 7:17

Well, it gave me a wonderful opportunity, personally, to delve into areas of fashion that I had never considered before. Because everything that is in this book has to have a specific date on it. That's actually pretty rare in fashion history. But what I've noticed is that when things survive with a date attached, there tends to be a really good story behind them. So those are the stories I tell in the book. And oftentimes, for example, things were saved because somebody died in them. Some of my favorite pieces in the book are things that have bullet holes or bloodstains because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. But that's why they have survived. It's not because they're beautiful or expensive or have a designer name attached to them. It's because of circumstances of history. The book covers from 79 AD, when Pompeii was buried by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius right up until 2018, right before it was published. And it covers all seven continents, as well as under the sea and outer space. Most costume history books and exhibitions can't do that. Because it would it would be completely unwieldy, to try to get all of that into one book. But by actually narrowing the focus down to this extremely specific criteria, I was able to broaden it in other ways.

Ted Fox 8:34

And you started to touch on it there, but I wanted to ask you about the research for a book like this. Because for people listening to this, you literally do go day-by-day through the entire calendar year, giving the history of a piece of clothing tied to that date, often with an accompanying photo. And I'm wondering the how of how you actually do that, and how you tie clothes to a specific date, particularly when you're dealing with something that's more anonymous and not--like, there's the hat Abraham Lincoln was wearing when he was assassinated, and there's the great photo of Jackie O on the cover of the book. But when you're dealing with more anonymous artifacts that have come through, how do you approach figuring out a date to tie them to to tell that story?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 9:21

Well, normally they come into a collection with the date attached, but it's often for a very odd reason--you know, like somebody was shot. There's a purse in the book that was carried by the only civilian killed at the Battle of Gettysburg, for example. Had she not died, that purse probably would never have found its way into a museum collection. Having worked in museums and in fashion history for about 20 years, I knew of a lot of these pieces that were out there that had these really interesting stories that had these dates attached to them. So I had enough that I felt like, Okay, I could write a book proposal, and maybe there's a book in here. (Ted laughs) I didn't actually start out planning to cover every day of the year; the idea was sort of maybe 100 things worn on this day to begin with. But when I pitched it to my editor, she said, Oh, and it's going to cover all 365 days, right? And I said, Right!

Ted Fox 10:18

Right, exactly! (both laugh)

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 10:20

And then I had to figure out how to do that. And how I did that was--well, a lot of trolling through museum online archives, looking for things with dates attached, but also digging into things like newspaper archives, looking for historic events that might have a piece of clothing attached them, going through diaries. In the book, I couldn't have a photo for everything, so some of them are literally a description, a line from somebody's diary or from a newspaper. I also do Worn on This Day on Twitter, and there's a photo with everything. And that's actually something I'd started before the book; that's where the book came from is from this Twitter account. But I started off that Twitter account not doing it every day thinking, Could I do this every day? Could I do a picture every day? Hey, could I do a book? And I just kept digging. And I've been doing the Twitter now for three years. So I haven't run out of objects yet with dates attached. (both laugh)

Ted Fox 11:15

So before I even looked, I guessed, as a lot of people probably would, that your entry for September 11th would have to do with 9/11. And the featured item is, it's a pair of shoes worn by a World Trade Center survivor. And you talked about these different things that were happening with people's shoes as they fled the towers, and almost 20 years later, it was an emotional thing for me to read. And I don't have any, you know, personal connection to 9/11 in that way, but it really was--it was a striking story. And I'm wondering if you can just describe a little, kind of the story that you told there, what you wrote about. And I think it really illustrates what we've been talking about. Because this was a detail in all these accounts of 9/11 that I personally hadn't heard before, and it's illustrated by an article of clothing that really makes the history and the horror of that day more palpable when you're reading it 20 years later.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 12:18

Yeah, the 9/11 Memorial Museum actually has more shoes than any other category of object. And that's not an accident. Your footwear made the difference between life and death in a lot of cases on 9/11. They have a lot of shoes that are blood-stained or melted or just covered in filth. Not all of them made it out of the building. I chose one worn by a woman who did. She had a brand new pair of heels. She was on, I think, the 96th floor, and she had to walk down all those steps. She took off the heels to navigate the stairway. But then of course when she got to the ground, there was debris everywhere and glass and rubble, and she put them back on, walked north through Lower Manhattan to the Hudson pier and got a ferry home, and realized when she got home that her shoes were covered with blood. Because of course, they were brand new shoes, and she'd walked all that way and had blisters, probably other people's blood on them, as well. A lot of 9/11 survivors said that they permanently changed their footwear choices after that. They don't wear heels to work anymore; they wear comfortable shoes that they can run in if they have to.

And I was really struck on January 6th when the two women who--the two staffers, the two female staffers who carried the electoral college votes out of the chamber when Congress was attacked, both were wearing flats. And they were interviewed later, and they said, Well, we've worked in the government so long, we have so many bomb scares that we've learned not to wear heels to work because you've got to go down all those stairs. And I thought that was really interesting. and something that echoed what a lot of 9/11 survivors said. And again, that's a detail where as soon as you see those shoes, you kind of know what happened that day. It's like the Jackie Kennedy suit. She wore that suit in public seven or eight times during Kennedy's presidency. But nobody remembers those other times because it's so intimately tied up with the events of that day, and it automatically takes us back in time to that day.

Ted Fox 14:28

Right. And then--so that's the entry for September 11th. September 12th, the next day, you jump ahead to 2010, and it's the meat dress that Lady Gaga wore to the VMAs. (Kimberly laughs) And it seems exactly like what you're kind of talking about and going for in using date as the criterion for the book. Because this is--I can't think of two things that would be any more different, and they're just kind of adjacent and dwelling next to each other in this.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 14:55

Yes. And you know, for some days I had about 20 great pieces to choose from, and I had to make some really hard decisions. Others, I was really struggling to find something; literally nothing of interest happened that day involving fashion. (laughs) But in the end, I tried to put together a combination of pieces that would tell the story of fashion in a meaningful way, and that would relate back to each other in meaningful ways. So I wanted to get certain things in there and wanted to make connections between pieces that might not get made in a different kind of book. For example, Queen Elizabeth's coronation and the Duke of Windsor's wedding are one day apart when you look at them in a day-by-day situation. And those two things are so intimately connected. If he had not married Wallis Simpson, she would not have become queen.

Ted Fox 15:52

Right. So I wouldn't ask you to pick a favorite date in fashion history from your book. But you mentioned earlier that, you know, you have this conversation with your editor, and now you're thinking, Okay, I have 365 days to fill. And so as you're researching it and writing it--and you kind of went into, you said, you know, some of these new areas that maybe you hadn't explored as much before--were there any surprises or unexpected turns that either you really connected with or that really stuck with you as something kind of, Wow--I do this for a living, I'm a fashion historian, and this is something really kind of new and different that I didn't expect to find?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 16:33

Yeah, definitely. I mean, I'm not an athlete by any means, but some of my favorite pieces in the book are sportswear and things worn, you know, at the Olympics or to perform various physical feats. And that's why they got saved, like the the kangaroo leather shoes that ran the first four-minute mile. That was really interesting for me. Especially women's tennis is very well-represented in the book because that's where a lot of the struggles about women's fashion and women's bodies have been played out very publicly throughout history. So that was very new to me. I mean, I don't have much of a background in sneakers or sportswear. (Ted laughs) But I was able to include a lot of those. My favorite pieces, though, are the ones with the bloodstains and the bullet holes, the ones where somebody died, because those tell the most moving and dramatic stories. And you know, like you said, reading the 9/11 piece, it will move you to tears. And there are others where I, you know, I cried when I was writing them. The Hiroshima school uniform is probably the one that was hardest for me because I had to read a lot of diaries and eyewitness accounts of what happened in Hiroshima. And the fact that this piece has survived and that they let me include it in the book is really important to me and really, really meaningful to me.

Ted Fox 17:56

Well, and I mean, you know, when we talk about maybe fashion or clothes at times being taken for granted, I mean, you think about everything that happens in our history, it's happening to people, and they're wearing something. And it's like this, you know, regardless of whether it was purposely chosen for that occasion or just what you happen to be wearing that day, I mean, it is the framing for everything that happens in our lives in a lot of senses, even though maybe we don't always think of it that way.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 18:28

For a long time, I'd wanted to write a book about fashion and history. Because this is all true, but it's very hard to explain that these things are so integral to our perception and our memory of history. Things like Jackie Kennedy's pink suit, things like the Pearl Harbor watch, they instantly transport us back in time to these places in a very visceral way. But I felt like I couldn't tell that story; I had to show it. So this book is showing it and giving people a chance to encounter these pieces that have been speaking eloquently from the past to the present for a long time. I mean, I quote Virginia Woolf in the book, when she visited the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and saw Nelson's uniform that he was wearing when he died at the Battle of Trafalgar, and this was in the '20s. And she's talking about how moved she was by this and how it took her back in time. And she felt like she was there on the Victory. And that's equally true today.

Ted Fox 19:28

Yeah. So for this past year, you're a 20-21 National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar. What does that mean when you're an NEH Public Scholar?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 19:40

That was a wonderful surprise and a huge thing for me personally and professionally because it's essentially a grant that gives me a chance to spend a year working on a dream project of mine, which is a biography of [an] American fashion designer called Chester Weinberg. And so I'm deep into that. I'm having a wonderful time, and it's the kind of thing that probably isn't going to be a bestselling book--although it would be nice if it was--but I wouldn't be able to get a book contract to write this. So the NEH has very generously helped me do that.

Ted Fox 20:14

So what's--I mean obviously, you're writing a whole biography about him, so there's a lot there--but someone like me, who doesn't pay as much attention to fashion, like there'd be certain designers whose names I would recognize, but this isn't one. So what about him--who was he and what makes him such an interesting subject for you?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 20:34

Well, I have to say that even people who do know a lot about fashion don't know who he is. (both laugh) I had never heard of him until I had a very random encounter with one of his pieces, you know, in museum storage and thought, Who is this? I have to know more. So don't feel bad if you've never heard of him.

Ted Fox 20:51

(both laugh) Okay, I appreciate that.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 20:52

But I call him the Halston you've never heard of. He was a contemporary of Halston, and Bill Blass, Calvin Klein. He was really sort of in the top five American designers, he didn't quite crack the top three, but it was sort of, Bill Blass, Geoffrey Beene, Donald Brooks, Oscar de la Renta, and Calvin Klein, and Chester Weinberg in in the late '60s. And his pieces are very typical of the late '60s, but also very much wearable today. And I'm very excited to kind of introduce people to them because he's just got great style and great taste, and I think is a really appealing designer, as well as a very compelling subject for a biographer. He had a fascinating life that parallels the rise of Seventh Avenue in many ways. So it's sort of a history of American fashion told through the lens of this one designer.

Ted Fox 21:47

Yeah. Very cool. I know you talked earlier about things that tend to get preserved, and one of the things that does tend to get preserved are wedding dresses, and I know you wrote a book about wedding dresses, too. And I'm not as familiar with that one, but was that kind of a wedding dresses around the world and the way they're different in different places, or what was kind of the focus of that one?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 22:14

It's called The Way We Wed: A Global History of Wedding Fashion. And it was published in December by Running Press, who published Worn on This Day. And it's kind of a sequel to Worn on This Day. Obviously, wedding dresses tend to survive with a date attached. So I found a lot of them as I was researching Worn on This Day, and I only could use a few because otherwise it would have been a wedding dress book, and that's not what I wanted to write. But when it got published, I thought, well, why not do the wedding dress book now because I found all this wonderful material. And it's not just wedding dresses; it's, you know, grooms, it's bridesmaids, it's mothers of the bride, it's wedding guests, it's going-away dresses. So much of what we think of as being very traditional in terms of wedding fashion is actually quite recent. Like, the white wedding dress, for example, relatively recent phenomenon, whereas many of the things that we think we just came up with, like having the wedding week or the rehearsal dress or the, you know, the reception dress, those things actually have a very long history. So it was fun to get into that in the book.

Ted Fox 23:19

That is interesting. Have you found in your career--and you were talking about, you know, trying to when you're making the case for how clothing relates to history--have you encountered--I don't know if this is a philosophical question about being a fashion historian--but have you encountered resistance over the years? Or where you feel like you have to make the case with people, you know, wanting to dismiss clothes or fashion as, Oh, well, that's not the same thing as studying the history of these battles or whatever else, where you kind of have to also do some education just to kind of prime the pump, so to speak, to say to people, This is really actually integral to who we are and where we came from?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 24:09

For sure. It definitely happens in academic settings, not so much with the general public and museum visitors and readers; they get it. But in terms of what gets funded, you know, who gets hired, that does tend to bias more traditional forms of history. And fashion is also what we call interdisciplinary. It covers lots of different kinds of history: women's history, economic history, you know, social history, royal history. So there's not--it doesn't fit neatly into its own box the way, you know, maybe traditional economic history or political history would. I come at it from an art history perspective, but it's much more than that. And it tends to kind of fall through the cracks in terms of traditional academic structures because universities don't have a fashion history department. They might have anthropology or art or history. It doesn't really belong in any of those.

Ted Fox 25:10

I was gonna say, Those darn universities. (both laugh) See, that's why we are promoting it. We actually have--I haven't talked to her in a long time, but we have a faculty member here, Linda Przybyszewski--who was originally like a--I shouldn't say originally--is a Constitutional law scholar but also is a fashion historian.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 25:29

Yeah yeah yeah.

Ted Fox 25:29

And has kind of like pursued these two interests simultaneously, which I think is very cool.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 25:34

Yeah, there's more and more great work being done in lots of different disciplines. So I hope that's changing. But it's a wonderful way to draw people into history.

Ted Fox 25:44

Yeah, for sure. I mean, it's such a literally tactile way to draw people into history of, like, these things that we continue to--I mean, they look different, but that continue to be a part of our lives every day. That hasn't changed. So yeah, I can see that bridge-making there for sure.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 26:03

Now, the pushback I get from non-academics is, Well, why are you making this political? Fashion is fun and frivolous. Why are you trying to make this so serious? I'm not making it that way. (laughs) That's just what it is. And what it has always been.

Ted Fox 26:19

Kind of as we're wrapping up here, someone who is listening to this--I mean, speaking of what we were just talking about, who has maybe never really stopped to consider fashion, or consider what our clothes say about us or our ancestors, our values, different cultures, cultures that are different from our own. What would you want them to take away from this conversation in terms of how they think about the place that fashion and clothes, I mean, really relates the human story?

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 26:52

I always think of fashion as communication. It's nonverbal communication that we are all participating in, whether we realize it or not. We are all communicating with others, and we're all interpreting fashion all the time. And I think once you adjust your mindset to think of it that way, you're a lot more careful about what you wear. (laughs)

Ted Fox 27:11

Reminds me of the scene early in the Devil Wears Prada where Meryl Streep's character is saying to Anne Hathaway, You think you aren't participating in this, but really, by you choosing and thinking not to participate, you are also making a statement that you are putting out there for the rest of the world to consume. So I really like that idea of, it is a very prominent way in terms of how we communicate about ourselves.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 27:38

Absolutely. That's a great scene and fashion historians love it. (both laugh)

Ted Fox 27:42

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, thank you so much for this. I had a lot of fun talking to you about this today.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell 27:46

Me too, Ted. Thank you for inviting me on.

Ted Fox 27:49

(voiceover) With a Side of Knowledge is a production of the Office of the Provost at the University of Notre Dame. Our website is withasideofpod.nd.edu.